Try These Guitar Rut Busters When All Your Solos Sound The Same!

Do This When All Your Guitar Solos Sound The Same

A lot of aspiring blues guitarists find themselves stuck playing the same blues improvisations over and over again.

This is normal, but you do need to have strategies to get yourself out of this rut.

Try these guitar-rut busters when all your solos sound the same:

If you want to learn more about taking your guitar solos to the next level, check out the free guide on How To Play More Advanced Guitar Solos.

And if you liked the video about getting out of a guitar rut, don’t forget to subscribe by clicking on the ‘youtube’-button below so you can get notified of the latest blues guitar video lessons:

Do You Want To Build Up Your Blues Guitar Playing Step-By-Step In A Logical Way?

In my Online Blues Guitar Lessons Program, I guide you every step of the way to blues guitar mastery.

Sound Like Carlos Santana - How Santana Uses The Major 6th To Create Exotic Guitar Solos

Carlos Santana’s Secret Note Explained

How does Santana ignite that exotic feel in his guitar solos?

It all boils down to one note!

In this video you’ll learn how Carlos Santana adds the major 6th to a basic minor pentatonic scale to create his magical guitar solos:

If you want to learn more about taking your guitar solos to the next level, check out the free guide on How To Play More Advanced Guitar Solos.

And if you liked the video about Carlos Santana's secret note, don’t forget to subscribe by clicking on the ‘youtube’-button below so you can get notified of the latest blues guitar video lessons:

Do You Want To Build Up Your Blues Guitar Playing Step-By-Step In A Logical Way?

In my Online Blues Guitar Lessons Program, I guide you every step of the way to blues guitar mastery.

Learn Blues Guitar Licks – Blues Guitar Licks Lesson

How To Master And Conquer Any Guitar Lick And Develop Your Personal Sound On Guitar

By Antony Reynaert

Do your guitar solos sound like you’re just going up and down a scale? Would you like to sound different from your peers and have your own distinctive sound on guitar? In this article you will learn the exact process great guitarists use (whether they know it or not) to master guitar licks and make them their own.

You may have had the joy of copying or learning a guitar lick, but did you really learn that lick inside out? Chances are you’ve only gotten 30% of the full potential a lick can bring to your guitar playing, as being able to play it is only were the learning starts. After following the steps in this article you will know how to get the full potential out of every guitar lick you learn.

What Great Guitarists Think About When Learning Blues Guitar Licks

STEP 1 - Build Your Vocabulary Of Licks

Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for creating melodies and solos so learning them is crucial for improvising. However, in the end it is the way you put these blocks together what makes your solo sound like music. The process of learning how to really internalize guitar licks starts with seeing and experiencing how great guitarists study licks themselves.

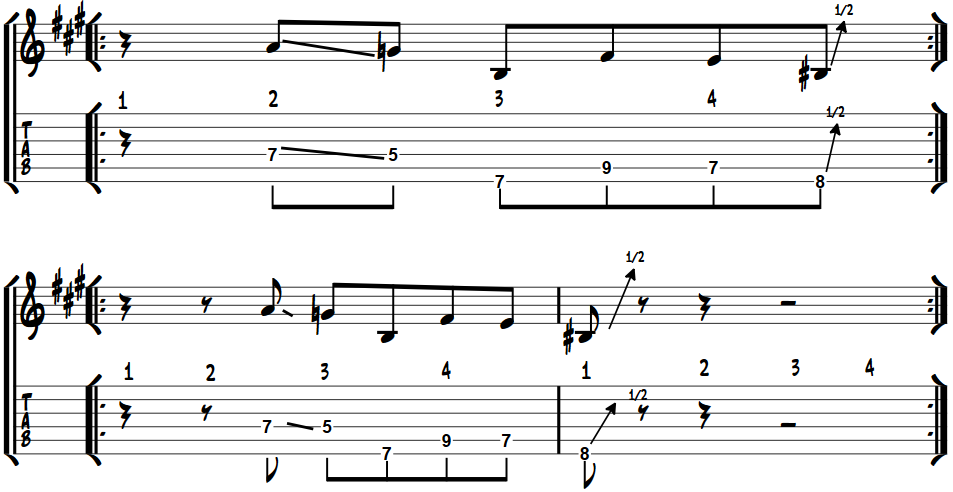

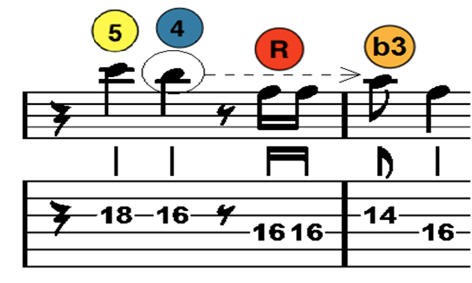

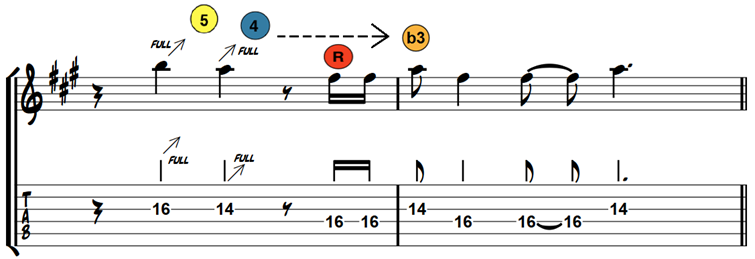

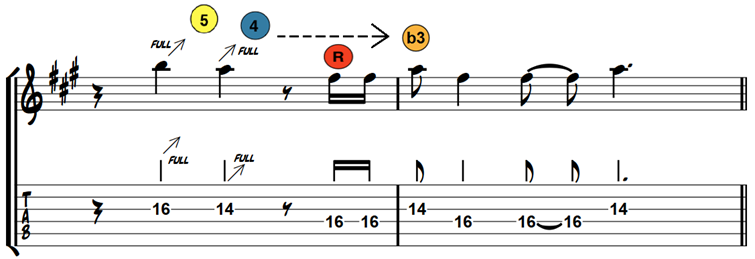

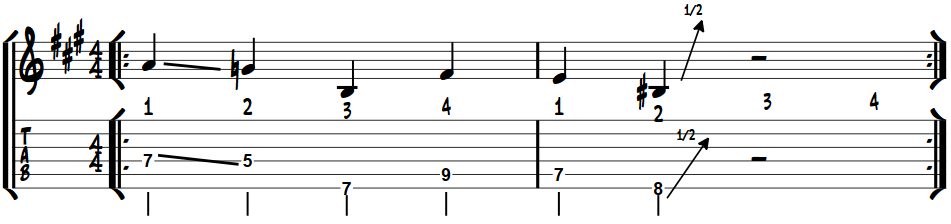

We will use the lick below as an example to go through the 5 steps. Of course you can use as many other licks as you want to repeat the process afterwards and improve your skills even further.

Make sure you play this lick more than just a few times without making mistakes (play it without tempo, every motion isolated from the next motion). This is because we first need to get used to playing this lick and to the way it sounds.

STEP 2 - Break Down The Lick Until Nothing But The Core Is Left

It is of crucial importance to know in what context your lick can be used. We want to be able to use it in different songs/situations and not only when we play the song we took it from. So we need to break it down and understand why it works. By doing so the lick will also be much easier to remember. The lick from the example is one I took from a solo by John Mayer, it occurs after the second chorus of his song Vultures (album Continuum). In this case the lick is being played on an F#m chord, so you could use this lick whenever you play over an F#m chord in your own improvisation.

Experienced guitarists don’t play random licks when they improvise, they know which notes will sound best over each chord. So with our lick it is important to know what these notes actually mean within the chord of F#m. In my Guide on How To Play The Most Awesome Licks Over Any Blues Chord you will learn exactly how to play the best sounding licks over chords instead of using one scale over an entire chord progression.

* R = Root note (red)

b3 = 3rd note from the relative scale (orange)

5 = 5th note from the relative scale (yellow)

With these colors we’ve indicated the chord tones. Note that with bended notes I don’t take the starting point into consideration, the note you end on is the approached note (the one we land on) so it is the one we should pay attention to. To get a better overview I wrote down the lick without string bends, the notes that are written are the ones the string bends ends on, the note that eventually sounds.

NOTE: depending on your level of knowledge of music theory the below description might sound somewhat abstract. If this is the case I would recommend you to read this article about Chord Tone Targetting.

The first three notes are 5 4 R, which would be a perfect arpeggio downwards if 4 would be b3, so you could say the b3 is substituted by the next note from the scale (4 comes right after b3). This creates some tension because our ear expects to hear the b3 instead of the 4. The b3 is being played in the next bar so the tension is resolved. At the end of the lick the two last notes (R & 3) are repeated.

The relative scale here is the F# Dorian scale (R 2 b3 4 5 6 b7). Take note that every note fits in the minor pentatonic scale of F# (R b3 4 5 b7), which is used a lot in blues guitar soloing.

If we look at it from this point of view, we could analyze it as follows:

When playing this lick we start on the 5th note from the scale and play the scale descending (downwards in pitch) from there on. As explained above we are skipping the b3 (instead playing the 4) to go to the root and then play the b3. Look at the color coded chord tones above the tablature to follow the analysis from above:

STEP 3- Build The Lick Back Up To Establish Your Personal Sound

Now that we’ve broke this lick down to understand and remember it, you could already use the lick while improvising if you’d practice it the right way. Now we will start changing the lick to get different versions or variants of it, so that we can take this to the next level and achieve our own unique sound.

1. Transpose

Change the key of the lick to a key you are familiar with and practice it.

1a. key of Am

1b. key of Em

You could also try to play it in different octaves, as shown in the beginning of the article. Choose 1 or 2 variations that you really like and make it your own (a good test is to record the lick and listen to it while you play the related chord). Choosing the lick/variation that you like and practicing it will give you your own sound while improvising. The choice of lick or variant is something highly personal and can be different for everybody.

STEP 4 - Internalize The Lick So You Can Play It Blindly

Up until now, all this work is merely theoretical exercise. If you want to use what you’ve learned you need to practice it so that you can play it blindly. Also it is important to be aware of the context in which you can play the lick. Practice both the original lick and your own updated version to get the maximum result out of your work. Take a chord progression and practice your lick over the chords where it is possible. Play your lick over every chord in this progression that fits (major – minor - 7th – etc.) While Step 2 was all about analyzing the lick, here we are internalizing the lick, so it is important to use your ears so you can hear how the lick sounds over each chord you are playing. You’ve started with something that is “borrowed” from another guitarist and – using the 5 steps outlined in this article - you’ve already made something that is completely personal.

STEP 5 – Steer Away From Becoming A One-Lick Pony

Go forth and take licks from your favorite players, learn them well and try to find at least one variation from the steps above. Take long licks, short licks, parts of a lick, glue one lick after another, etc. You’ll find that doing this will strengthen your improvising skills and help to create your own unique sound on the guitar.

In addition to this article I would recommend you to study my Guide on How To Play The Most Awesome Licks Over Any Blues Chord.

Break out of your blues guitar soloing cage with this Essential Blues Guitar Soloing Lesson.

How To Improve Your Timing - Timing Exercises For Guitar

Timing is crucial for a blues guitarist and you won't be able to hear or feel how sloppy your playing is if you don’t understand the concept of timing. You will truly improve and test your own limitations if you follow the examples from this article. In order to play your solos and chords tight you will need to have some part of the 'rhythmical spectrum' in your ear. In other words, you will need to develop different possibilities in terms of rhythm and timing.

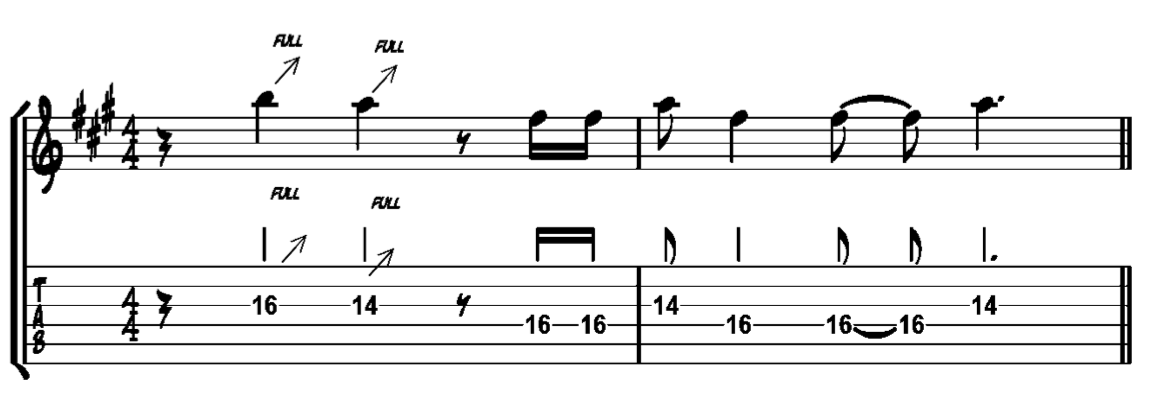

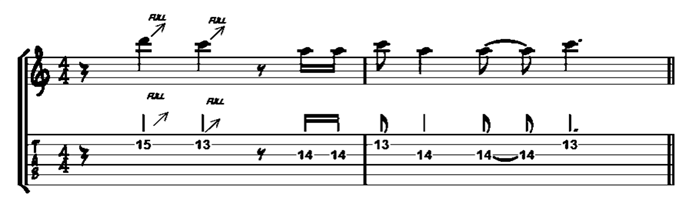

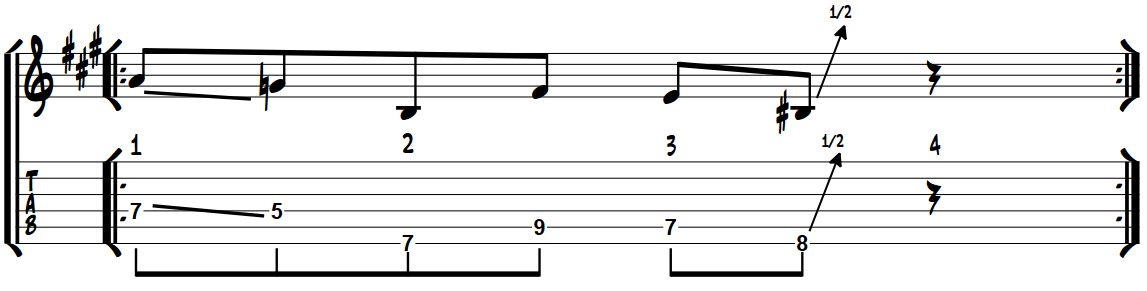

Your most effective tool to work on timing is your metronome or drum loop. If you truly want to nail this material and become a master of timing then the ultimate test is to count every beat aloud whilst playing or practicing with a metronome. Here you’ll find a lick I’ve made, it starts on the 1st beat and is made up of all quarter notes. The term quarter note refers to the length of the note being that this one lasts for an entire beat in a bar of 4/4.

You will not be able to play tight if you are not able to have control when you play with different note values, such as quarter notes, 8th notes, 16th notes. If you can not switch between these note values with ease, this means your timing will be off and you won't improvise anything interesting. The good news is that you can improve your timing. Take the example above and apply the same method in your own improvisations, licks or rhythm playing. In order to use this concept freely you need to practice and experiment with it. Getting your timing right is not only technical as being able to hear the beats and rhythms in your head and feel these in your body is as crucial as being able to execute them.

Playing tight can also be seen as playing steady, it is about playing any kind of rhythm, perfectly placed, in any part of the bar. When playing rhythm it is important to not slow down or speed up. If there are parts in the bar where you aren’t able to play steady then you need to develop your feeling and hearing. Try and practice the following licks. These are very specific variations of the lick above to help you develop your timing.

In this example you see the same lick moved one 8th note further in the bar, so instead of starting on the 1st beat it now starts between the 1st and 2nd beat (called 1&). You should be comfortable playing a lick like this, no matter on which part of the bar you start it.

Also check if you can play this lick but starting on the other possible places in the bar. You should repeat each version consecutively in order to really get it in your ears. If you want to be able to incorperate these skills while playing freely (improvising or comping) the first step is to use a blues guitar lick you already know.

In trying these examples you’ve probably noticed that is hard to apply this timing to the same lick or that you didn’t get it right as fast as you thought you could. This shows how much you should work on timing. Note that this information can be applied to other licks, solos, improvisational and rhythm guitar parts.

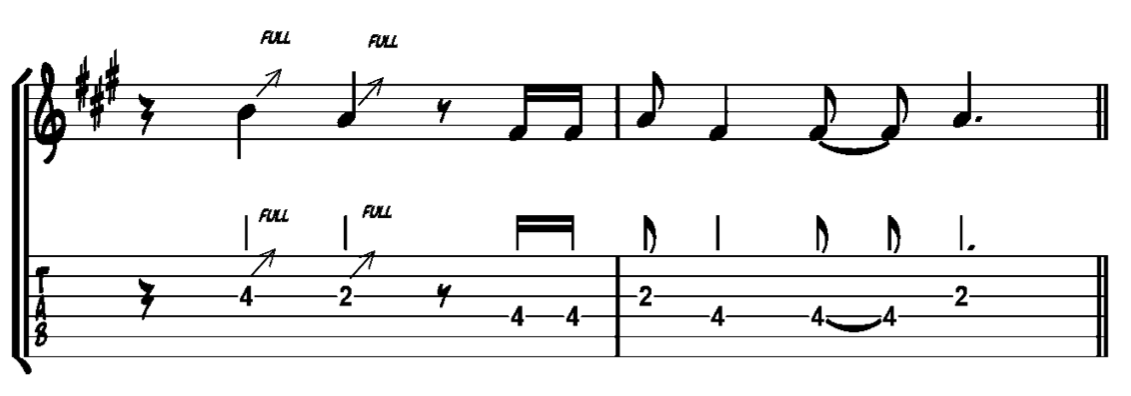

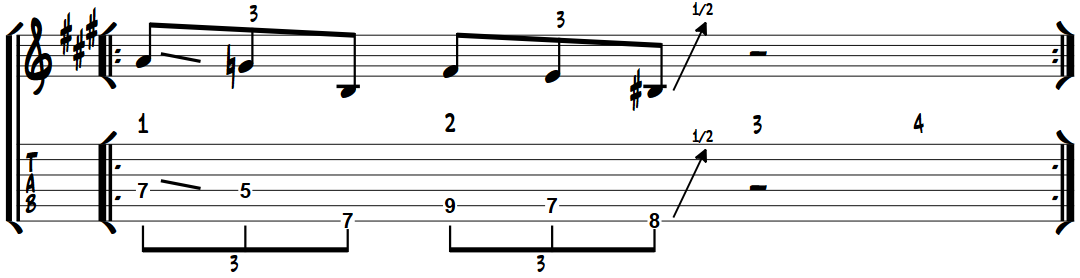

Here I’ve put the same lick in 8th note 'triplets'. A triplet is a note that fits thrice in a beat, as opposed to the regular 8 notes that only hold two notes per beat. Here you’ll find a TAB with audio:

Make sure you can play it tightly and then move the lick so it starts on the 2nd, 3rd or 4th beat of the bar like in the previous examples with the 8th notes.

Developing a feel for triplets is a must for every blues guitarist at some point especially in learning how to play shuffle rhythms. It is highly recommended to practice scales in this way. Try playing them in triplets and also combine triplets with 8th notes. You can for example ascend the scale in 8th notes and descend in triplets.

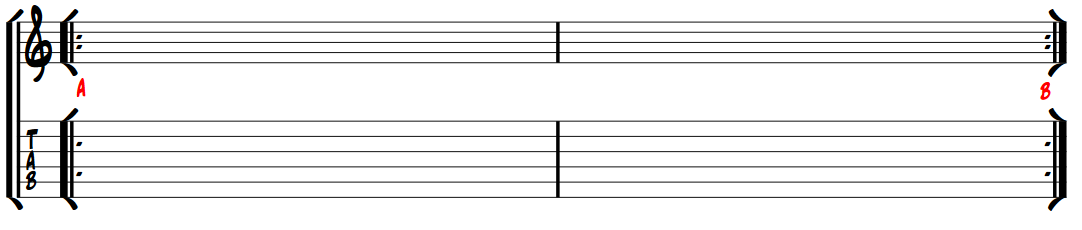

Can you play two bar phrases? With this I mean very rigidly start playing a phrase in one bar and end it in the next bar. It doesn’t matter whether you improvise or play a lick you already know. So start after A and end before B.

Many amateur players solo “over the bar line” without really understanding it. This lack of timing awareness causes solos to sound shallow like a chain of meaningless notes. To avoid shallow sounding solos try to keep playing two bar phrases for a while with a metronome or backing track as practice. The ultimate way to improve fast is to record yourself and check back to make sure you’re not cheating by playing over the bar lines. From a musical point of view two bar phrases will give your solo a question and answer feel. Also it will make sure you leave spaces in your solo and don't overcrowd it with meaningless notes. Starting your solo off with two bar phrases gives you a lot of possibilities to build up to be interesting and dynamic.

When you’re just jamming you are free to play over the bar line, this may even sound great. The important thing is to become aware off the difference between fitting a phrase in one or more bars or starting your phrase before the bar line. Now you are studying or practicing a concept to develop your ears and feel of timing. A huge part of timing is really knowing when you play over the bar line instead of blurting out notes and licks. Trying to pick up 'where you are' in the bar from listening is a big part of timing.

When someone’s talking without really reaching a conclusion but rattling on without leaving some space between sentences. It is not pleasant to listen to, right? It is the same way with playing. Practice making phrases in two bars and become accustomed to play anywhere in the bar in order to gain control and become an experienced blues guitarist.

Robben Ford Blues Guitar Lesson – How To Use The Altered Scale

Playing In The Style Of Robben Ford - The Ultimate Guide To Using The Altered Scale In Blues Guitar Soloing

By Antony Reynaert

Do you want to be able to use gut wrenching outside sounds in your blues guitar playing? Wouldn’t it be awesome to be able to fully understand what the altered scale is and how you can use it in your blues guitar improvisations? You’ve come to the right place.

There are multiple resources talking about how the altered scale is related to superlocrian, which is also the 7th mode of the melodic minor scale. Unless you have a major in music theory, all this information is overly confusing, leading you to think that playing in the style of Robben Ford is very difficult.

Demistyfying Jazz Guitar Soloing And The Altered Scale

That is why we will approach this topic from a down-to-earth approach. To do so, we will start to look at how guitarists, and musicians in general, approach the topic of advanced blues and jazz guitar soloing. The great thing about blues soloing is that we can add specific scales that sound very tense, jazzy, etc. at specific times in a chord progression. Think about those guitarists like Scott Henderson (you might want to look this one up if you don’t know him yet) who make their audience turn their head with a sudden frenzy of notes that sound totally ‘out there’.

To understand how these guitarists use scales like the altered scale it is important that you have a basic understanding of how chord tones and scales relate. Basically, a scale exists out of two types of notes:

1. chord tones

2. tensions (also called extension notes)

Chord tones are the tones that are being used when we play a note that is in the chord we are playing over. For instance if we are soloing over the A7 chord, we can use these chord tones: A, C#, E and G. This is because these notes are in the chord. In music theory these notes are often referred to as consonant pitches. Tensions are notes that are not in the chord we are playing over, but are in the scale we are using. So for instance, if we are playing over the A7 chord using the A mixolydian mode we are using these notes:

A B C# D E F# G

The bold notes in the scale above are the extension notes, since they are not part of the chord, but they are part of the scale. In music theory these notes are often referred to as dissonant pitches (level 1). So to recap we are having these pitches:

1. chord tones = notes that appear in the scale AND also in the chord (consonant pitches)

2. extensions/tension notes = notes that appear in the scale but NOT in the chord (dissonant pitches (level 1)).

Experienced guitarists target chord tones when they want to play safe, outline the chords they are playing over, or if they generally are looking for a more stable sound. On the other hand, they target tension notes if they want to add… well, tension.

How Altered Tones Can Give Your Solos That Twisted Heartfelt Feel

These tension notes have a more dissonant feel to it, but we can even take this one step further. To create even more tension, we can ‘alter’ the extension notes. In this way we are creating a third group of possible notes to use when soloing:

1. chord tones

2. extensions/tensions

3. altered tones

These altered tones gives the lick or passage in the solo a really tense, jazzy feel.

The altered tones consists out of:

- The b5

- The #5

- The b9

- The #9

This is where the altered scale comes in. When using the altered scale we are playing: chord tones coming from the dominant seventh chord mixed with altered tones. Yes it is true that this altered scale is related to the superlocrian scale, which is the 7th mode of the minor melodic scale. But approaching the altered scale in this way can be confusing and I would not recommend to study this relationship until you really understand how the altered scale is build up and how it can be used in a blues setting.

What The Altered Scale Really Is When You Omit All That Confusing Jazz Theorist Noise

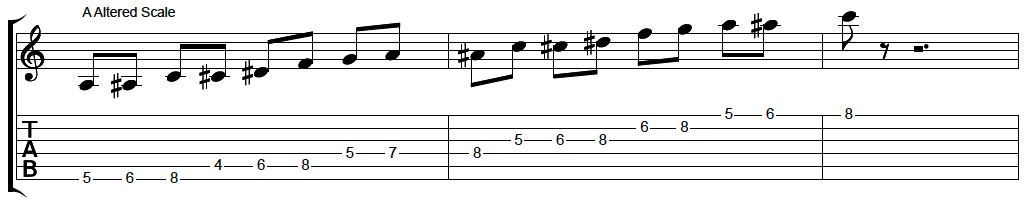

Understanding the altered scale is not all that hard when you approach it from the dominant seventh chord. In the image below you see the chord diagram for the A7 chord:

5 8

A7

Now look at the following image, which features the same chord tones from the A7 chord, but now along with the altered notes.

Remember, these altered notes are really notes that aren’t easy to use over the dominant seventh chord they are being played over, but when we use it together with the chord tones they become very cool sounding jazz outbreaks out of the normal scales we could use. This all results into a very jazzy sound that is great to use when you want to build tension. Think of the altered tones as ‘outside notes’.

The Altered Chord – How And Where To Use The Altered Scale

Music is all about tension and release, so because the altered scale is full of tension we should use it at strategic places in the chord progression where we can easily release that tension again. We can use the altered scale at any point in a chord progression where we can use an altered chord. An altered chord, like the altered scale, is a chord that uses both chord tones from the dominant seventh chord and an altered tone.

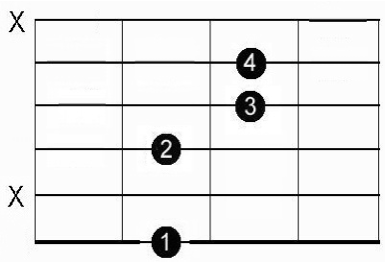

Take for instance this A7#5 chord:

5

A7#5

This chord basically consists out of the A7 chord tones and also uses one altered tone; the F note in this case, which is the #5 in this example). This chord typically gets used when going from a chord that is a fifth lower than the previous chord. For instance, in a regular 12 bar blues progression this can happen at different points:

A7 A7 A7 A7

D7 D7 A7 A7

E7 D7 A7 E7

When moving from the A7 chord in bar 4 to the D7 chord in bar 5 we are moving a fifth lower. This also happens when going from the E7 chord in bar 12 to the A7 chord in bar 1 again. At these two points in a regular 12 bar progression we can use the altered scale/chord. It is important that you understand that we don’t need to play the altered chord in order to play the altered scale over it. This is because we can ‘imply’ the chord instead of actually playing it when using the altered scale. For instance, when using the altered scale over bar 4 in the progression from above we are actually implying the altered chord since we are using the altered tones in the scale. However, we can insert the altered chord at these places in the progression even though we don’t need to play the altered scale over it.

A7 A7 A7 A7alt

D7 D7 A7 A7

E7 D7 A7 E7alt

As you can see above, an altered chord is sometimes referred to as ‘alt’ instead of writing the full chord name. This is because, as you learned above, we can use both the b5, #5, b9 and #9 to alter a chord, the choice is yours. For now, we can use the A7#5 chord and the E7#9 chord at these places to make it more defined, as in the progression below.

A7 A7 A7 A7#5

D7 D7 A7 A7

E7 D7 A7 E7#9

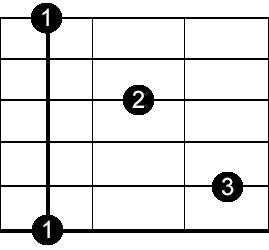

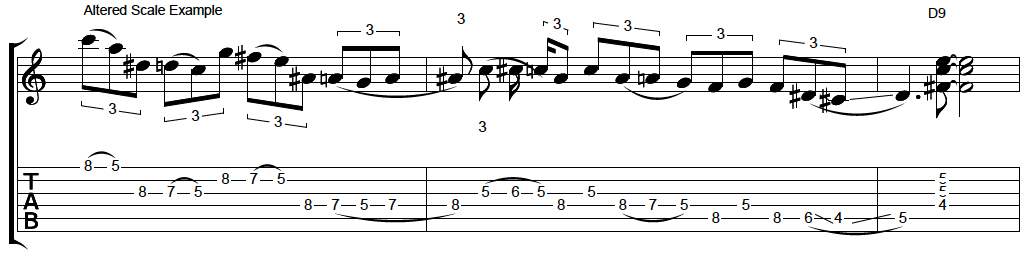

When you play this chord progression try to listen for the added tension in bar 4 and bar 12 that the altered chord creates. Over this chord progression we can use the altered scale in bar 4 and bar 12. In bar 4 we can use the A altered scale, while in bar 12 we can use the E altered scale. Remember that we are using the notes from the dominant seventh chord + all altered tones when playing the altered scale. Here is an example lick featuring notes from the altered scale. The first 8 notes start out with another scale, but starting from the 4th beat of measure 1 all notes are derived from the A altered scale:

Listen to the audio example of this Altered Scale Lick.

If you want to learn how to play licks that best outline the chords you are playing over a blues (great guitarists do this all of the time) I recommend to study my How Great Blues Guitarists ‘Spell Out’ Changes When Playing Over Blues Chords.

Get started today with my Best Lesson On Blues Guitar Solos